Generally the glyphs used as phonetic elements were originally logograms that stood for words that were themselves single syllables, syllables that either ended in a vowel or in a weak consonant such as y, w, h, or glottal stop. Maya glyphs were fundamentally logographic. These variations most often appeared when they would better fit the surface being inscribed. In place of the standard block configuration Maya was also sometimes written in a single row or column, 'L', or 'T' shapes. Another example is the ampersand (&) which is a conflation of the Latin "et". Conflation occurs in other scripts: For example, in medieval Spanish manuscripts the word de 'of' was sometimes written - (a D with the arm of an E).

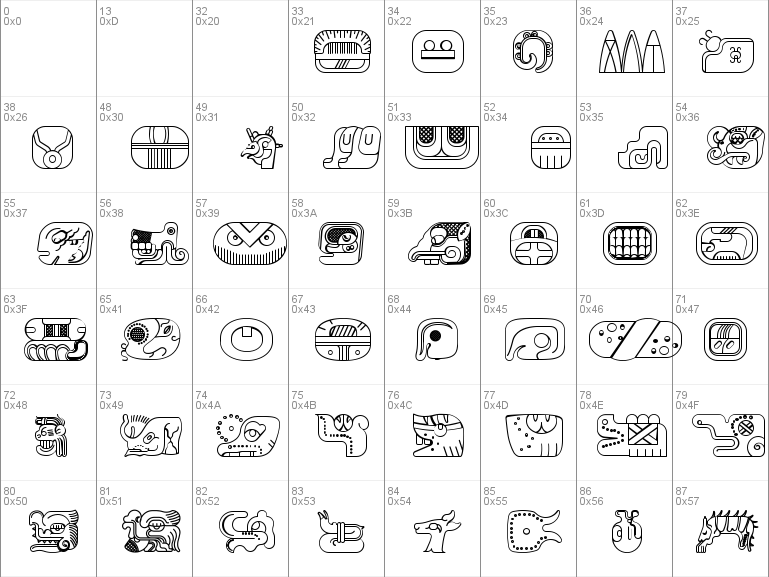

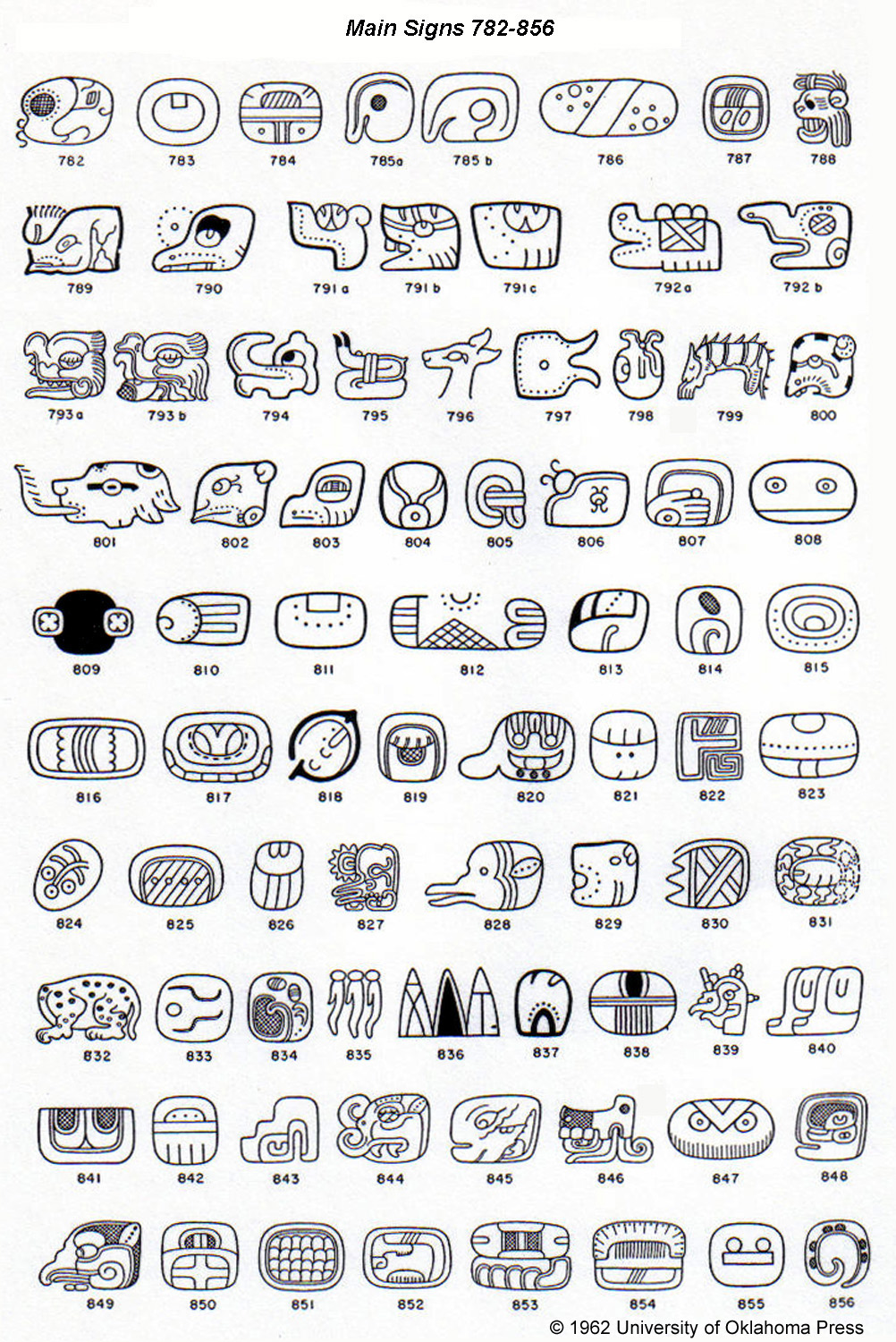

Also, glyphs were sometimes conflated, where an element of one glyph would replace part of a second. However, in the case of Maya, each block tended to correspond to a noun or verb phrase such as his green headband. Within each block, glyphs were arranged top-to-bottom and left-to-right, superficially rather like Korean Hangul syllabic blocks. For example, half a dozen apparently unrelated glyphs were used to write the very common third person pronoun. There was ambiguity in the other direction as well: Different glyphs could be read the same way. (It's customary to write logographic readings in all capitals and phonetic readings in italics.) It is possible, but not certain, that these conflicting readings arose as the script was adapted to new languages, as also happened with Japanese kanji and with Assyro-Babylonian and Hittite cuneiform. For example, the calendaric glyph MANIK' was also used to represent the syllable chi. Individual symbols ("glyphs") could represent either a word (actually a morpheme) or a syllable indeed, the same glyph could often be used for both. The Maya script was a logosyllabic system. About 90% of Maya writing can now be read with varying degrees of certainty, enough to give a comprehensive idea of its structure. Carved and molded glyphs were painted, but the paint has rarely survived.

Maya writing consisted of relatively elaborate set of glyphs, which were laboriously painted on ceramics, walls or bark-paper codices, carved in wood or stone, or molded in stucco. However, if other languages were written, they may have been written by Ch'olti scribes, and therefore have Ch'olti elements. There is also some evidence that the script may have been occasionally used to write Mayan languages of the Guatemalan Highlands. It is possible that the Maya elite spoke this language as a lingua franca over the entire Maya-speaking area, but also that texts were written in other Mayan languages of the Peten and Yucatan, especially Yucatec. It is now thought that the codices and other Classic texts were written by scribes, usually members of the Maya priesthood, in a literary form of the Ch'olti' language. Maya writing was called "hieroglyphics" or hieroglyphs by early European explorers of the 18th and 19th centuries who did not understand it but found its general appearance reminiscent of Egyptian hieroglyphs, to which the Maya writing system is not at all related.Īlthough most Mayan languages utilize the Latin alphabet, Maya writing has received official support and promotion by the Mexican government and is taught in universities and public schools in some Mayan speaking areas. Maya writing used logograms complemented by a set of syllabic glyphs, somewhat similar in function to modern Japanese writing. Writing was in continuous use until shortly after the arrival of the conquistadors in the 16th century CE (and even later in isolated areas such as Tayasal). The earliest inscriptions found which are identifiably Maya date to the 3rd century BCE in San Bartolo, Guatemala. The Maya script, also known as Maya glyphs or Maya hieroglyphs, is the writing system of the Maya civilization of Mesoamerica, presently the only Mesoamerican writing system that has been substantially deciphered.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)